Emerald mountains emerge from the clouds, so close to the tip of the aircraft’s yellow-and-orange winglets that I couldn’t help but wonder what the rate of survival would be, should the plane crash this close to land. As the pilots adroitly guide us through spiked peaks and narrow valleys, I found myself counting the doors on houses perched on steep hillsides.

I have come to the tiny Buddhist kingdom of Bhutan, possibly the closest thing to the fabled Shangri-La on this planet, to do something that few living Bhutanese have done in their lifetime: walk the restored Trans Bhutan Trail, a 403-kilometre stretch that connects the country from east to west. For centuries, it served as the nation’s lifeline, frequented by monks, pilgrims, soldiers, traders, and messengers to cross the lands, but the building of Bhutan’s first major highways in the 1960s spelt the path’s end. Now, it has been painstakingly unearthed, and I am among the first travellers to hike this historical footpath.

Bhutan is often spoken of in the same breath as Gross National Happiness, a concept that thrust the kingdom into the limelight in for its prioritisation of well-being and sustainable development. It has long eschewed the influences of the world beyond its borders, although modernisation has doggedly crossed the country’s threshold and shows no signs of slowing.

It also looks—and feels—like a place out of time. Ancient fortresses, white-walled chortens, and timbered farmhouses dot the landscape. Rushing rivers cut through gorges, and everywhere you turn, there are mountains—great, big, towering giants playing second fiddle to the dramatic Himalayas. Its blue pine forests are lush, untamed, and soul-stirring. It is in these woods that I was determined to unravel the oft-cited mysticism shrouding Bhutan.

Even the mere arrival into the country signals adventure. Landing in the nature-hugged Paro International Airport, at 2,235 metres in elevation, is a hair-raising exercise in placing your fate in a higher power—or in the hands of Drukair pilots, who weave and bob their way through the scenery in manual mode. If that does not feel thrilling enough, the audacious manoeuvre is said to be so technically demanding that flights in and out of Paro are only allowed by daylight and during good visibility to minimise risks—just one of the many different, almost-beyond-belief things about Bhutan that feel so very on-brand.

Immersion into Bhutan’s otherworldliness is immediate. In the airport arrival hall, exquisitely hand-painted portraits of the royal family smile benignly, the very picture of elegance and poise, arresting travellers with their gazes. I am here a day after Blessed Rainy Day, an auspicious holiday that marks the end of the monsoon season. It celebrates the rain as a cleansing element—a symbolic holy rinse for the earth and humanity, so to speak. In Vajrayana Buddhism, water is no small thing—it embodies purity and life, is used to bless devotees at temples, and is offered to spiritual figures at altars. We’re off to a good start.

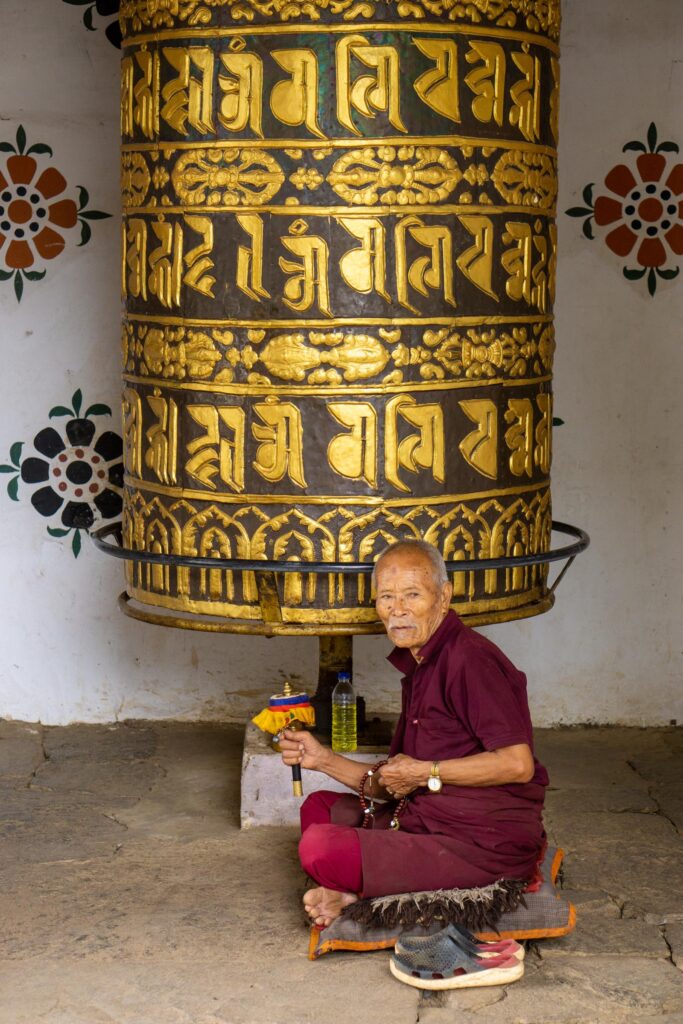

A delegation of monks strides through the baggage claim, their red robes swishing with purpose. People are dashing to catch them before they sweep through the exit and out of the airport, bowing their heads low upon approach. Well prepared and well trained, the group does not break its stride, and one monk amongst them is methodically handing out blessings on the go, lighting tapping the tops of heads as he passes.

“Who was that?” I ask Damchoe, the guide of our group, who is waiting outside the airport with Pema, our fearless driver for the week. He had just draped a white silk scarf—a khata—around my neck, a common welcome greeting in Bhutan. “Oh, that was a very important, very holy monk,” he replies. He grins, “I got a blessing from him, too.”

I am chuffed. Not even 10 minutes into Bhutan and I had already spied my first Buddhist celebrity. It was like encountering a film star at the airport. Little did I know then I would soon breathe the same rarefied air as a Bhutanese prince, walk in the footsteps of the Divine Madman, and sit next to the prime minister of Bhutan at dinner, all before the week was out.

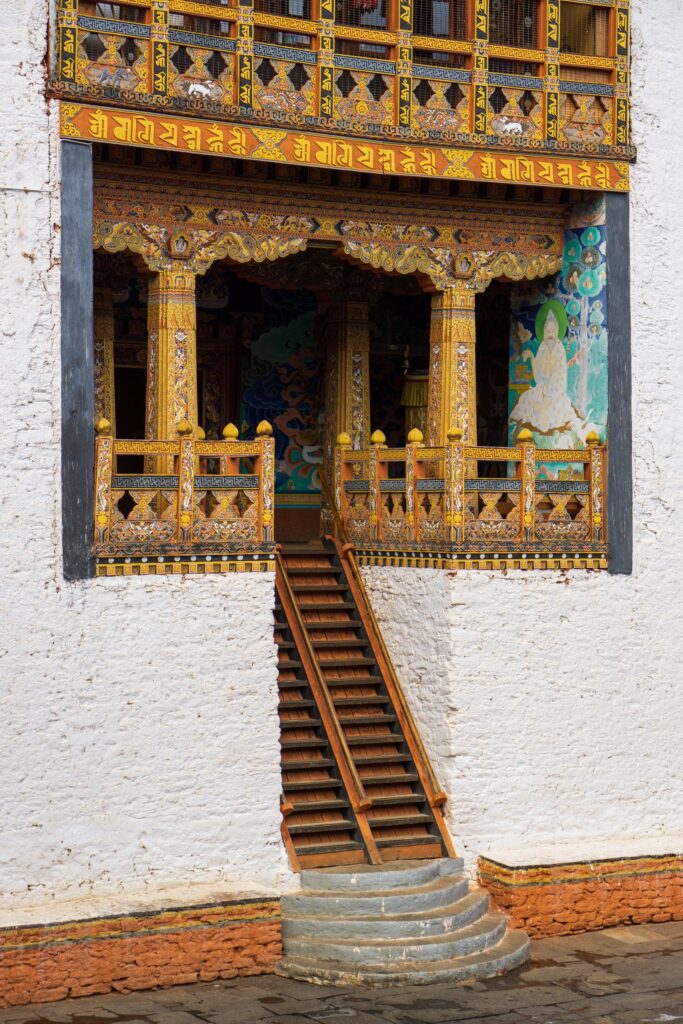

In the “Land of the Thunder Dragon,” perched high amongst the Himalayas, said to be home to the gods, it’s entirely plausible for one to feel close to divinity, or to feel the urge to seek out a deep spiritual connection, even if only for the duration of your stay. It’s easy to wrap your head around the natural beauty of Bhutan when you think of it as a gift from the heavens, though in reality, it’s the result of active environmental conservation efforts. Over 5,603 species of flora thrive here, 678 species of birds, and 60 percent of the land is constitutionally protected from logging and urban development. Bhutan even royally decrees that the construction of buildings must adhere to the same traditional design standards, ensuring the architecture is harmoniously in sync with the local cultural heritage.

I am witness to all of this first-hand on the second day of my journey. Our first hike on the Trans Bhutan Trail sees us begin the day at Dochula Pass, where much milling about was done at the Druk Wangyel Café to warm ourselves with hot drinks and ward off the biting cold—and in hopes of catching glimpses of the Himalayas. No such luck. It’s an overcast day, and the sky, as far as the eye could see, is well swathed in dense clouds. 108 memorial chortens, built in three concentric circles to honour a bygone battle, sit silently in the background, keeping watch as we march off in single file into the wilderness.

Nothing about our first hike on the Trans Bhutan Trail screamed “look at me, look at me”—and that is part of its beauty. It is matter-of-factly embedded into the countryside, an indisputable part of the landscape. And it was a steep descent. We start at 3,100 metres, but soon plunge into a humid jungle, where verdant vines slither up the trunks of trees and a fertile terrain promises all sorts of creepy crawlies hiding in the bushes. Damchoe reaches into the folds of his gho, the Bhutanese national dress for men that has a tuck reminiscent of a kangaroo’s pouch, and pulls out bottles of water and KitKat bars. We pause briefly to peel off our jackets—the climes change drastically in as little as an hour—and it is here that I first meet some of the people responsible for making the Trans Bhutan Trail walkable again.

Clad in bright orange jumpsuits, the desuup are a group of volunteers, also known as “guardians of peace” for the service they provide for the country. Desuup are mobilised for all kinds of reasons; to respond to natural disasters, assist at Covid clinics, deliver vaccines, and even offer crowd-control support at large events. In short, they are indispensable.

In anticipation of the reopening of the Trans Bhutan Trail, the desuup were tasked with the responsibility of restoring the pathway, building new bridges across raging rivers, beating away overgrowth, and repaving the trail for future use. It was a task that took several years to complete, but there was no better time for it than during Covid-19, when the country withdrew even more than before and closed itself off to foreign visitors.

But the desuup had help—lots of it. In fact, the restoration of the trail was initiated by His Majesty King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck to connect communities across the kingdom, and the undertaking was generously supported by Sam Blyth and the Bhutan Canada Foundation, and the Tourism Council of Bhutan. Excavating the trail itself was a challenge: “60 years is a short time in our natural history, but an age in the life of a trail,” Blyth recalls, remembering the numerous town hall meetings held around fireplaces at night, talking to village elders to pinpoint the original path during the research phase of the project.

Scarce written records or mapping exist as the result of the oral language tradition, but from the conversations “came an archaeological-like excavation that revealed rutted pathways, worn stone steps, chortens or signposts, and all kinds of religious icons. Not only was the trail overgrown but many stairways had subsided. Bridges collapsed.” It was a “mammoth task” to rebuild the trail in record time. “More than 400 kilometres of trail was cleared, 10,000 stone steps cut and installed, and 18 bridges built over 115,000 feet of vertical, sometimes in very challenging weather,” says Blyth. All this was done to give back to the people an “enormously important part of Bhutan’s history and culture, to bring life and commerce to some of the remotest communities in the country, and allow Bhutanese—particularly the youth of this country—to walk in the steps of their ancestors.”

Hours later, we emerge at Thinleygang, just shy of the border to Punakha, where we made camp on a plateau overlooking a monastery sitting by a cliff. Nearby, our first spiritual excursion awaited. Toeb Chandana is high on the list of must-visit pilgrimage sites in Bhutan, where there is no lack of holy destinations. It is said that the arrow of the Divine Madman landed in this sacred spot deep in the valley, and it’s been a venerated landmark ever since.

Getting to Toeb Chandana, however, was no easy feat, and involved delicate navigation along steep, narrow dirt roads hugging the mountainside. Our driver, Pema, navigates the bends and winding roads with a dexterity that would feel at home on the tracks of Formula 1 racing. Swerving around landslides on the national highway and gently nudging a bulky 12-seater along cliffside roads barely wide enough for a man and a cow to walk abreast, he demonstrated an expert level of driving skill that kept us hale and hearty. Damchoe, our tireless guide, kept us entertained—and our minds far from death—with his singing.

Veering off the Trans Bhutan Trail to see religious and culturally significant sites became the order of the day. (Well, it did used to be an ancient pilgrimage path, after all.) Landmarks like the golden Buddha Dordenma and Punakha Dzong lie along the way, although making it to the oft-photographed Tiger’s Nest requires a considerable detour. But often, the simple spirituality of the land came to find us as we walked: in the rhythmic clanging of a bell from a hydro-powered prayer wheel, providing a steady beat to the trickling stream of water; in the solemn chanting of monks, heard in echoes; in the sharp rustle of rainbow prayer flags flapping in the wind. In the deep embrace of nature, living in the moment and letting your mind wander is effortless. Mindfulness is at your fingertips.

To walk the Trans Bhutan Trail is to learn its history and appreciate the resilience of its people. Bhutan, surrounded on all sides by soaring mountain ranges, appears as an elusive Himalayan kingdom, where time has (almost) stood still. Famously, it has never been colonised, and, as a result, it has retained a distinct national identity that the country’s constitutional monarchy works hard to protect. A fantastical kind of mysticism envelops this little-visited place, where mythical creatures like the garuda are intricately painted on the exteriors of houses. Consider Bhutan’s national animal, the takin, which sports physical characteristics akin to the gnu, goat, sheep, and cow (yes, all of the above). It also has a giant nose and can weigh up to 350 kilos. It looks more like a caricature of a mammal rather than something you would find in real life—which feels like the running theme of things you encounter in Bhutan.

An enduring fun fact about the country is that television only (officially) arrived in 1999, followed by the notion that there are no traffic lights at all, even in the capital city of Thimphu, where cars are directed manually by traffic wardens from a circular island in the middle of a roundabout. Cows roam the streets and road signs are hand-painted with quippy phrases like “No hurry, no worry” and “Speed thrills but kills.” Yet, you can spy bald-headed monks discreetly tucking smartphones into the folds of their deep red robes, and luxury wellness brands like Amankora and Six Senses staking their claim, providing top-end lodgings to the influx of moneyed visitors undeterred by Bhutan’s “high value, low impact” tourism fee.

For all its “sounds too good to be true” positives, the kingdom is not without its troubles. Bhutan’s economy suffered during the pandemic lockdown, and the standstill of tourism played a large part in the struggle; Thimphu plays Tetris with buildings under construction as the city barrels its way to urbanisation; and the younger generation is looking outwards, beyond the country, for greater opportunities. But the deep love and respect for the community and for the land persists, and there’s a rawness and sincerity to Bhutan that is difficult to fabricate. It invites you to peel back the layers and return to the basics of what matters most—taking care of yourself, the people, and the land around you. A simple enough concept, but seldomly put into practice in our modern-day lives.

“How are you enjoying the hike?” the prime minister of Bhutan asks. I smile toothily in response, dumbfounded. It’s not every day that you get to chatting with dignitaries.

We are back at Dochula Pass, where the grounds of the mountaintop café have been transformed into a reception party with tents sprawled on the greens. Musicians are playing on as dancers glide across the lawn, and hot bites and beverages are dished out liberally from a mess tent. Dr Lotay Tschering—the prime minister—is dressed in a striped gho with wide folded cuffs. A pin bearing the portrait of His Majesty the King is affixed to his chest.

He is in good spirits for someone who had just led a 4.5-hour switchback hike from Simtokha Dzong up to Dochula Pass, which sits at 3,100 metres above sea level. It was at this historic fortress-monastery in the hills of Thimphu that Trans Bhutan Trail was officially reopened. His Royal Highness Prince Jigyel Ugyen Wangchuck led a ceremony in the richly decorated inner sanctum of the sacred dzong accompanied by monks’ prayers and the flickering light of hundreds of butter candles—an intimate occasion that few were privileged to witness, and I amongst them. After the proper blessings had been made, we set off into the woods.

The lilting melodies of monks singing and their echoes around the valley carry me along the forested path, punctuated by the sound of a rushing waterway somewhere beneath us. A healthy fall of yellow and brown leaves blanket the ground. Red-robed youngsters in front of me—and behind me—effortlessly manage the same trail in worn plastic sandals at a brisk pace, while I work hard to keep up with them. I lost my group while taking a snack break, but a trio of desuup shepherd me along and we end up in conversation about our favourite television shows (theirs is the Japanese anime One Piece, by the way).

I plod through fields of hardy chillies, grown at a seemingly impossible elevation, forming the staple food to a spice-obsessed nation. Ema datshi, a stew of cheese and chillies, served with a side of locally grown red rice, makes an appearance at most mealtimes, but on today’s menu are perfectly ripe apples, freshly plucked from an orchard lining the side of the trail and tossed to me by my new desuup friends as we traipse through the loamy forest.

At long last, we emerge into a clearing, where the rest of the group had already crowded around a raised stone platform. Between them lay baskets of fruit and zaw (crunchy toasted rice kernels), canteens of scalding buttertea, and heaps of cups. Villagers from a nearby gewog (traditional village) had decided to meet us on the trail, offering humble hospitality in the form of refreshments as we were due to begin our ascent uphill. It was an excellent bit of planning on behalf of the Trans Bhutan Trail organisers—except that it was completely unplanned and had been, in fact, initiated by the villagers themselves, unbidden.

As I sip buttertea hot enough to burn my tongue and bite down on the sweetest fruits the season has to offer, I am moved by the generous disposition of the strangers I have met on the Trans Bhutan Trail, the simple bond formed over a shared repast, and the warmth of the people who give so freely. Connection permeated the air—the very kind His Majesty the King had envisioned when he set out to rebuild this cross-country path.

As we sit down to dinner later that evening and pepper the prime minister with questions, I think back to the journey we completed that day, and the question I left unanswered. But expressing these sentiments, in all its unpolished sincerity, is a task that feels momentarily insurmountable. Some things are meant to be felt, rather than said. And so, I sit, and listen instead, so I can remember this feeling of gratitude.

An afternoon at the Nalanda Buddhist Institute with principal Khenpo Dendup was the equivalent of receiving a crash course in Bhutanese Buddhism and its virtues, but it was the long days spent in conversation with our local guides while walking the solemn stretches of the Trans Bhutan Trail that really put the abstract spiritual teachings into perspective. Often, these lessons are nonchalant, casual comments, spoken humbly—and inspiring humbleness in the listener—such as this one by Karma, one of our group’s guides: “People think that wealth equals material possessions or money, but I find wealth in being compassionate, patient, and kind. I find wealth in the support of my community.”

A week is too brief to fully understand the wild, colourful, and nuanced heart of Bhutan, and too short to traverse the entire land in the footsteps of unflagging pilgrims. But the lessons of a lifetime, and the path to contentment, are within grasp, and walking even a small section of the Trans Bhutan Trail feels like taking one deliberate step closer to compassion and happiness.

Hiking the Trans Bhutan Trail is free, but travellers are encouraged to plan their journey directly with the not-for-profit social organisation Trans Bhutan Trail, as all profits from its guided tours support the maintenance of the trail and give back to the local communities. Guided tours start from US$300.

All images courtesy of Jen Paolini.