As I look over the releases from Watches & Wonders this year, I am struck by the general conservatism of the collections. This isn’t a bad thing—perhaps even an improvement over the predominance of Liberace-ready watches offered in Geneva last year. Amid this year’s restraint, however, what’s jumping out for 2024 is the sheer imagination and—I’ll just say it—wondrousness of the watches coming from brands that have traditionally, though not exclusively, catered to women. Watches from Cartier, Chanel, Chopard, Hermès, and Van Cleef & Arpels are blowing our minds.

For too long, watch aficionados have dismissed collections aimed at women as unserious. If you’re catching a whiff of gender trouble here, follow your nose. We’ve recently explored this dynamic in detail elsewhere, but to sum it up: Jewellery and fashion have long been women’s turf and highly complicated mechanical watches have long been men’s turf. That passé attitude is shifting. But it’s not just the 21st century’s blurring of gender identities or the rise of dude-bling that’s causing the change; it’s also the imaginative use of highly complicated mechanical works in collections aimed at women.

Image courtesy of Van Cleef & Arpels

I’m prone to gazing at the backside of a Lange Datograph with a loupe magnifier and experiencing sustained awe, but I am profoundly more wonderstruck when gazing on Van Cleef & Arpels’s brand-new Brise d’Été in action. This watch sends butterflies around the dial as violets dance in an imaginary breeze for 12 seconds before returning those tiny lepidoptera to display the time on a retrograde scale. Seriously? That’s way cooler than watching yet another chronograph total up the time I’m wasting watching it do so.

I don’t quite understand why some of us watch nerds will obsess over anglage—also known as chamfering or bevelling—found on a flat metal plate, but we will waltz past something like the dial on Chopard’s new Imperiale 36 mm watch. This dial is at least 20 times more interesting—not to mention more difficult to create—than a well-cut corner on a rhodium-plated brass disc.

Image courtesy of Chopard

I will quote from my colleague Carol Besler’s description of the Chopard Imperiale, because she put it so well: “The dial… is covered with a blue-green enamel background, dotted with a perfectly uniform pattern of white enamel and pink mother-of-pearl marquetry flowers. The centre of each white flower is set with an orange padparadscha sapphire and each pink flower with a diamond. The flowers and centre gems are surrounded by rims of 18-carat white gold, raised slightly above the dial. The resulting pattern mimics the quatrefoil floral motif in Venetian architecture, particularly in the Doges Palace.”

I’ve discussed at considerable length whether Seiko has accurately reproduced the exact grey of the 1965 62MAS dive watch dial for its US$1,100 (HK$8,615) homage, but the Chopard dial here actually deserves a lengthy discussion. In fact, this watch makes me want to learn more about how it’s made. If you care even a little about the handcraft coming out of the birthplace of Swiss watchmaking, Fleurier, then better not to waltz past this Imperiale from Chopard.

It’s not that watches like IWC’s Eternal Calendar aren’t blowing minds. In this new release, IWC has employed a massive gear that skips three leap years over four centuries to account for orbital anomalies, and the moon phase display only misses one day every 45 million years. That’s bonkers. But the IWC which has mastered leap years doesn’t really leap out when compared to Hermès’s Arceau Chorus Stellarum, which sends a skeleton horse and rider literally leaping across its dial.

Image courtesy of Hermès

Here I will refer you my colleague Victoria Gomelsky: “A pusher at 9 o’clock activates an animation in which the skeleton horse and rider—embodied in mobile yellow-gold appliqués, engraved and painted by hand—prance around the champlevé enamel dial whose colourful lacquer-coated motifs are adorned with applied rhodium-plated stars.”

The complications driving that horse around the dial would be enough to keep most mechanical watch nerds up at night with an illuminated loupe, but when coupled to the animation of a famous Hermès scarf designed by the Japanese illustrator Daiske Nomura, we’re looking not only at a triumph of mechanics but of aesthetics, imagination, and—to the extent that we care—creative brand extension with a cosmopolitan twist. Hermès is on fire this year.

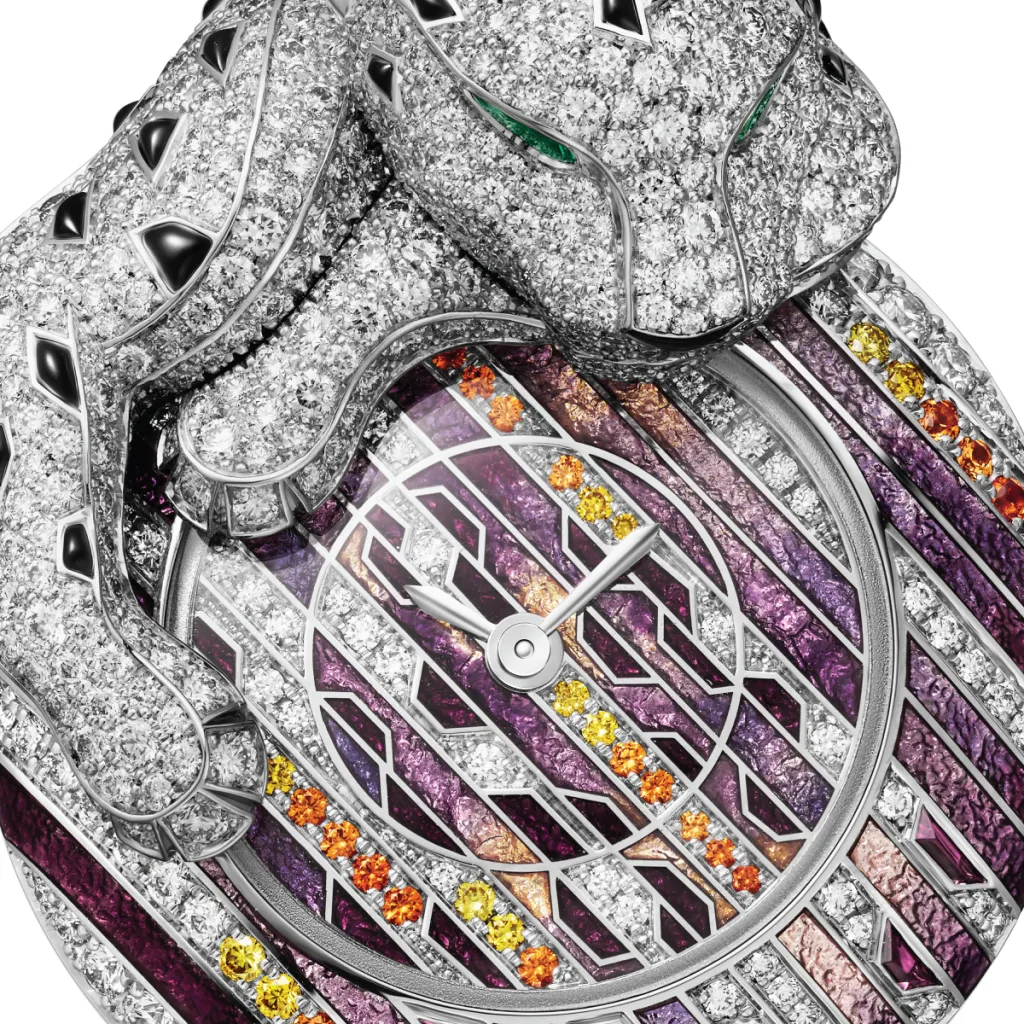

Cartier, meanwhile, has returned to its roots by delivering fresh versions of the Santos and revisiting its historically oriented Privé collection with some traditional Tortue offerings, which are just lovely. But if you want to be bowled over, you’ll have to check out Cartier’s bejewelled timepieces.

Image courtesy of Cartier

The famous Panthère is joined by an alligator in this year’s Animals collection, and while these creatures wrap themselves around a somewhat banal quartz movement (found in a majority of Cartier’s watches), the gem setting here ought to cause those who care about hand-cut metal micro-architectures to stop and consider what’s going on beneath the pavement. We’re looking at rhodium-finished white gold cut by hand to hold hundreds of top-grade tourmalines, sapphires, emeralds, diamonds, rhodolite garnets, spessartite garnets, and onyx. The technical skill of setting those stones in on par with, if not beyond, the finest horological handiwork.

Image courtesy of Cartier

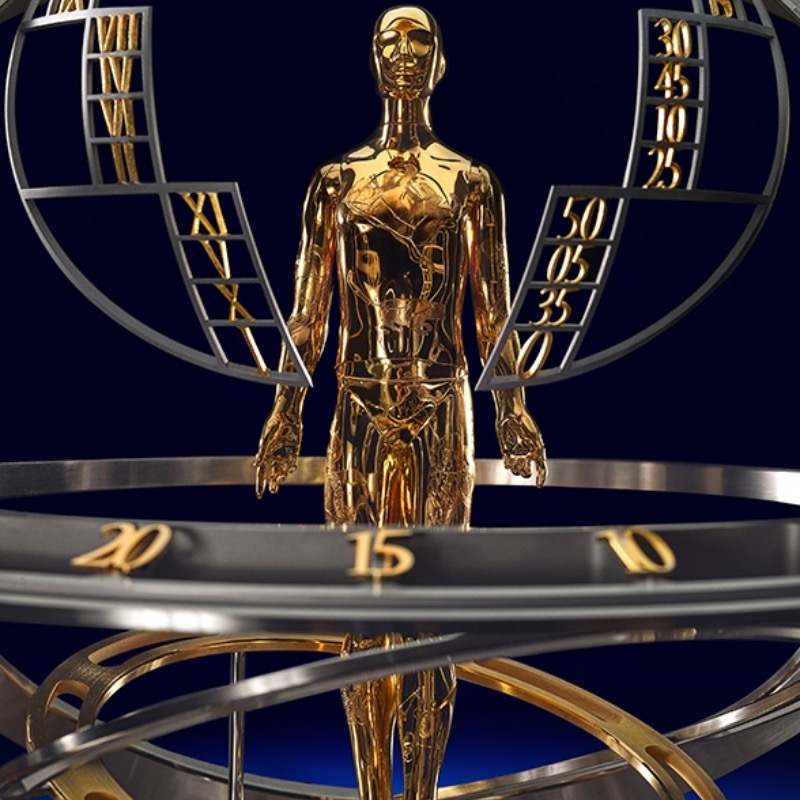

If Cartier isn’t convincing you that high mechanical art is on offer from feminine-leaning brands this year, we need only wander back over to Van Cleef & Arpels and consider their museum-grade clocks. The decorative craftsmanship alone astounds, but these clocks also perform jaw-dropping mechanical automations. With the Apparition des Baies, a crown of leaves opens to reveal a bird which takes flight as music chimes from within; when it’s all over, the bird lands and the leaves fold back up around it.

Image courtesy of Van Cleef & Arpels

Even more remarkable is the Bouton d’Or. Van Cleef & Arpels’s own description really captures what we’re seeing here: “A fairy, her face suggested by a rose-cut diamond, crowned with diamonds, and clad in a flamboyant rose-gold gown trimmed with blue lacquer, pirouettes in an enchanted dance upon a blooming flowerbed. She twirls thanks to the beating of her plique-à-jour enamel wings, delicately clasping a briolette-cut sapphire between her fingers.”

Image courtesy of Van Cleef & Arpels

Just to be clear: The fairy turns because it beats its wings. I still love the Lange Datograph, but come on…

Admittedly, some of those watches appear a little on the traditional side of high horological art, but Chanel has countered with two Boyfriend models that display their beautiful mechanical systems as remarkably as any of the big skeletonised offerings this year. Meet the Chanel Boy-Friend Skeleton X-Ray Pink with a transparent sapphire case and the Skeleton Pink with an 18-carat beige-gold case set with 38 baguette-cut pink sapphires. The exposed Calibre 3 is an in-house manual-winding mechanical skeleton movement. No unexposed quartz or second-tier auto-winder here. This is manual high horology on full display.

Image courtesy of Chanel

Because of the gracefully laid-out gear train that harmonises visually with the timepiece’s ever-so-subtly branded skeletonised dial, this watch outshines every open-worked or skeletonised watch I’ve seen this year. Seriously, I just looked again to make sure I wasn’t overstating my point, and Chanel has them all beat. Each of these Boyfriend Skeleton Pink watches is offered in a limited edition of just 55 pieces and features a quilted leather strap. (By the way, why aren’t there more quilted leather straps? That’s so chic.)

If it seems as if we are stating the obvious—that a flurry of sparkling gems and high handcraft outshines traditionally styled men’s watches—perhaps it bears mentioning that the timepieces we’ve selected here are neither entirely bejewelled nor are they the only bejewelled watches to be found at Watches & Wonders this year. Not even close, given the recent rise of bling. The point, we hope, is subtler: There is a creative freedom explored and expressed among these brands that have historically created watches for women. Their sense of whimsy and their ability to realise it in metal and stone has been hard-earned through consistent effort, decade after decade—which isn’t an entirely inaccurate definition of the horological arts.