In the summer of 2020, at the height of the pandemic, an Asia-based client approached De Beers with a request so detailed and idiosyncratic that even a company accustomed to bespoke commissions for a discerning clientele could quite reasonably have been stumped. “She wanted something very specific,” says De Beers Jewellers CEO Céline Assimon. The client’s exact wishes dictated a D-flawless diamond with a mix of personally significant, symbolic proportions and numbers (presumably for the carats and facets), as well as a guarantee of a certain type of light reflection and refraction—a boutique-bought diamond, no matter the cut, clarity or size, simply wouldn’t suffice. “We did not have and would not have cut a diamond in that way for stock,” says Assimon.

So De Beers unearthed a rough stone that could fulfill the requirements. The process from procuring the uncut diamond to setting the resulting finished gems in a pair of drop earrings took over a year, with the client involved at every step. As beautiful as the pieces turned out, the client acquired more than unique stones and bespoke earrings—she also scored one hell of a story. “The journey is more important, in a way, than the end product,” Assimon says. “You are going to be holding it in your family forever.”

More and more, high-jewelry clients are insisting on ever increasing thresholds of exclusivity and unparalleled bragging rights, making ego-centric demands that can be satisfied only by working with a rough diamond, cutting it to exact specifications and setting it in the design of their dreams. The escalating desires of VVIPs are shaking up a once rigidly hierarchical industry. Traditionally, mines would source rough stones and sell them to dealers, who would then have the stones cut and polished (either through their own companies or third parties) before selling them to high-jewelry houses to be turned into finished necklaces, rings and other pieces. Sometimes mines would cut the stones for dealers, and occasionally, in the case of extraordinary stones, jewelry houses would source their own roughs. Generally, however, each sector of the business stayed in its lane.

Today, everyone is rushing to carve out their own channel to deliver diamonds, even multimillion-dollar roughs, direct to consumers. Mines and dealers alike are usurping high-jewelry houses by putting rough diamonds in private clients’ hands to create one-of-a-kind pieces. Meanwhile, jewelry houses, including Graff, Van Cleef & Arpels and Louis Vuitton, are securing legendary stones as the foundation—both literal and narrative—of their high-jewelry collections.

Two new companies steeped in the business of mining, cutting and polishing stones have cropped up this fall to sell significant roughs straight to clients, bypassing the dealer and the jewelry houses altogether. Signum—a subsidiary of HB Antwerp, a Belgium-based supply chain and manufacturing firm specializing in cutting and dealing in high-end diamonds—is bringing roughs to clients for bespoke designs, while Maison Mazerea, a new venture from Burgundy Diamond Mines in Perth, Australia, is offering both uncut stones for bespoke pieces and high jewelry created in partnership with independent A-list designers, such as Parisian Lorenz Baümer, using diamonds directly mined, cut and polished in-house.

“What we’re trying to bring to our ultimate customers is something that’s absolutely unique, something that the person in the yacht next door doesn’t have.”

The bar for rare diamonds is already high, but Maison Mazerea is well positioned thanks to the established capabilities of its parent mining company. It will also source stones through mining partnerships in Canada, Botswana and other key diamond-rich countries. And, when the Argyle Diamond Mines, known for the world’s finest pink diamonds, closed in 2020, Mazerea promptly hired its renowned cutters. “We just cut a seven-and-a-half carat [diamond],” says Ravenscroft. “That’s prob- ably a two- or three-million-dollar piece of stone, and that came out of about a 14-carat piece of rough. Our next one is a 24-carat piece of rough, so we’ll be producing a larger stone with that.”

Mazerea will also feature unusual cuts, with fewer facets to show more subtle light refraction than modern cuts and more of the stone’s natural color, inspired by 17th-century techniques used for the French royal courts. (The brand name comes from Cardinal Mazarin, an important diamond collector and chief minister to Louis XIII and Louis XIV.) “If someone wants a marquise cut, they’re not going to get one from us,” says Ravenscroft. But for clients looking for an object and an experience out of reach for most, Mazerea will provide raw material for custom projects that fit within its untraditional aesthetic. “We can offer somebody a rough diamond, and they can come to the mine, they can meet the people. We can get into our cutting facility, and they can sit with the design and planning of the stone.”

While Maison Mazerea will also sell finished pieces in partnership with independent designers, HB Antwerp’s Signum is dealing exclusively in rough diamonds, offering every client complete control over their stone from its rugged nascent state to its glittering finale. The process can take anywhere from three months for a straightforward approach to a year or more for more complex projects, such as creating a unique cut complete with its own IP rights. Signum, like Maison Mazerea, is also well situated for this new business model: Its headquarters in Antwerp is where more than 86 percent of the world’s rough diamonds are traded.

Ahead of Signum’s official launch before the end of this year, a few early adopters were already finding themselves pleased with its bevy of rare stones. One client proposed to his fiancée with a rough during a hike in Gstaad, Switzerland. And no, the rock didn’t look like something he’d just picked up on the trail. “He set the rough diamond in a beautiful ring,” says Rafael Papismedov, managing partner and strategy director of HB Antwerp and Signum. “She was walking around with this ring for two months, and everybody was asking questions.” When the couple finally decided what to do with the stone, she had a hard time letting it go. “But then sitting there for hours with our [team], measuring angles, deciding on the length, deciding on where the light reflection is going to come from and how it’s going to look was such a beautiful process.

I think it’s such a beautiful way to start a marriage.” Another client was so happy with his initial two uncut gems, he transferred US$2 million to Signum to find a third. “He said, ‘Keep it and when you find me a stone, just let me know,’ ” claims Papismedov. “It was quite addictive.”

As far as addictions go, amassing a collection of million-dollar rough diamonds is a rather expensive habit, so lavish it almost seems suspect. But Signum is keeping a tight rein on its pieces, which will be 10 carats or larger and, as a result, in very limited supply. Prospective clients will have to go through a know-your-customer vetting process. In both high jewelry and high-end watches, brands often heavily research—and even interview—interested buyers and typically require an existing client’s referral before finalizing a transaction. “We don’t want to be a machine for money laundering,” says Papismedov. “We don’t want to be a machine for corrupt politicians to buy pieces to hide the value through us. We don’t want to serve any drug lords. That’s why at the beginning we’re going to launch this platform in the Western world, mainly on the West and East Coast of the US and expand slowly into Europe. When you join this [figurative] club in this community, you will be comfortable knowing that the people are sharing the same values.” Mazerea, like-wise, will be focusing on North America because, says Ravenscroft, “squeaky-clean production processes are less important in Eastern markets.”

As for the companies’ own ethics, both are encouraging clients to visit the mines and/or headquarters, so they can, in theory, meet the workers and witness the working conditions first-hand. Signum also uses block-chain technology to certify the origin and authenticity of the diamonds to protect against shady practices, such as Russian mines shipping roughs to India, where they are cut, polished and labeled as Indian to get around Western bans on Russian gems. “The idea is—and it plays very strongly to the provenance aspect—we know where the diamond came from because we mined it, and it never leaves our control until it ends up in the customer’s jewelry piece,” says Ravenscroft.

Both Mazerea and Signum will also donate a portion of the proceeds to aid the local mining communities. Signum is taking its progressive business practices a step further by holding its mines to heightened environmental, social and governance values—and raising the price as a result. “Everything you want to know about the mine, from the environmental impact to whether they are using diesel or solar panels, how they’re washing everything, what kind of chemicals are used, what kind of explosives—everything will be rated inside the price of the diamond,” says Papismedov. Governments’ and the mines’ sustainability efforts will be second. “The idea is to bring incentives to miners and to government to apply the highest standards in this world.”

Perhaps trying to get a jump on the competition, jewelry houses such as De Beers and Graff are already dialing it up notch. Graff acquired Lesedi La Rona (meaning “Our Light” in the Tswana language of Botswana, where the diamond was mined) for US$53 million. At 1,109 carats, it is the fourth-largest diamond ever found—so massive the company had to custom-build a scanner and imaging software to figure out how to cut it. Graff then used a laser to inscribe each of the 66 resulting stones with the name of the diamond. The markings are not visible to the naked eye but add a concealed layer of provenance. “They sold quickly,” says CEO François Graff. “Engraving them with their origin was our way of celebrating this once-in-a-lifetime find and giving our clients the opportunity to wear a beautiful piece of history.”

These top purveyors are not novices when it comes to roughs. De Beers Group began creating its own branded jewelry pieces in 2001 but has been producing and supplying diamonds to the industry since its founding in 1888 and accounted for an estimated 80 percent of the rough-diamond distribution until the beginning of the 21st century. Even today, it sells about 30 percent of the world’s rough-diamond production by value. Graff, founded in 1960, purchased its first major uncut stone in 1989, when it acquired the 320-carat Paragon, which yielded a 137.72-carat gem, the largest D-flawless diamond in the world at the time, and since 2000 has bought an important specimen nearly every year.

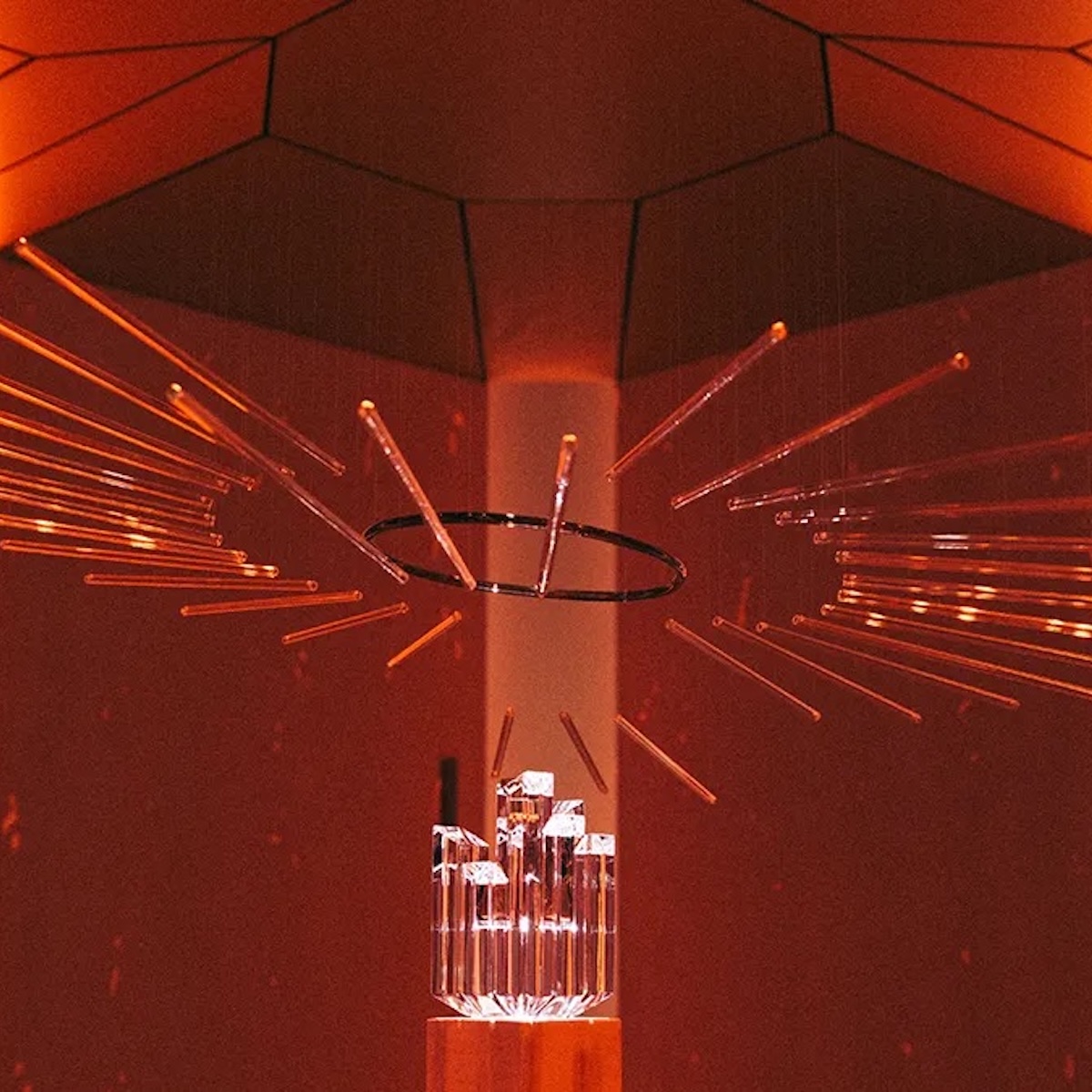

Such is the power of these stones, brands are now selling lifestyle products inspired by their gargantuan treasures. François Graff, whose father, Laurence, spent a year negotiating the deal for the Lesedi La Rona, says they “knew it had the potential to be a history-making stone.” Now Graff is milking the rock’s fame for all its worth, even offering namesake fragrances housed in emerald-cut crystal flacons meant to capture the essence of the diamond.

The idea that these billion-year-old rocks can create endless hype has enticed newcomers. In 2018, Van Cleef & Arpels, which has historically opted to buy stones already cut and polished, paid a reported $40 million for the 910-carat Lesotho Legend, the fifth-largest diamond ever mined. President and CEO Nicolas Bos says Van Cleef normally doesn’t buy roughs because they often yield diamonds of varying qualities—they may be the same color but not the same purity. “Here what was a bit special is that one of the dealers we have worked with for a very long time… saw that the quality was so high that it would probably be extremely consistent throughout the stone,” says Bos.

It took almost a year of planning—using scanners, CAD designs and the instincts of the cutters—before tools penetrated stone and another three years to create a high-jewelry collection, which debuted in July. It features 67 diamonds, ranging in sizes from 25.06 to 79.35 carats, from the original. “It just brings a whole other dimension to the maison’s provenance, which I believe consumers perceive as additional value and probably even brings that much more pull to the high-jewelry collections,” says Kristina Buckley Kayel, managing director of the Natural Diamond Council and former vice president of marketing and communications for Van Cleef & Arpels. “I think when you have the likes of Van Cleef doing something like this, we’ll probably be seeing more of it.”

Not long after Van Cleef acquired the Lesotho Legend, rivals started digging into the rough-diamond market. In 2019, Louis Vuitton snapped up the 1,758-carat Sewelô, the second-largest diamond ever found (outdone only by the 3,106-carat Cullinan mined in South Africa in 1905), followed by the 549-carat Sethunya in 2020. Both were uncovered at Lucara’s Karowe mine in Botswana, where the Lesedi La Rona was also unearthed. Although Vuitton has been making high-jewelry collections since 2009, it was a surprising move for a maison more widely known for selling luxury leather goods and ready-to-wear. While the French house won’t divulge how much it paid, the Sewelô alone is estimated between $6.5 million and $19 million. The resulting stones will be reserved for made-to-order diamonds, allowing VIP clients to be involved in the process from start to finish. The cutting and polishing of the Sewelô and Sethunya diamonds, said to be complex, will be spearheaded by HB Antwerp, the parent company of Signum, the same firm now selling its own roughs straight to clients.

The big maisons and jewelry houses, with the exception of very few, if any, don’t have any knowledge of transforming those diamonds from rough to polished,” claims Papismedov, unsurprisingly. Those houses, he adds, are accustomed to outsourcing the job almost 99 percent of the time, so will face a steep learning curve. “Definitely, it’s great PR and it’s an interesting story, but they don’t have the in-house knowledge to do it. Their involvement is mainly about putting a piece of metal around it and very rarely about creating the diamond itself.”

What will it mean for big luxury houses as dealers, cutters and miners start dipping into each other’s respective client pools? Those concerned with brand names will, of course, remain loyal to the traditional jewelers. But for the vaults that already have everything money can buy, controlling the entire creation of a jewel, from the ground to the skin, may well be the final frontier.